promoting the child’s present and future quality of life

July 2025 has a comprehensive campaign to foster children’s rights which is designed to encourage the active participation of all member organizations and to produce measurable results. ACSSWRPR 2025 co-operates closely in this area with the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), the International Labor Organization (ILO), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), other Global Union Federations (GUF) such as IUF and BWI, national trade unions, union centres and various non-governmental organizations such as the Global March Against Child Labor.

Bureau of Education, Education International, the NGO Group for the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the International School Psychology Association and the Office for the Study of the Psychological Rights of the Child (School of Education of Indiana University-Purdue University , Indianapolis), as well as numerous Danish national organizations. Approximately 2000 participants will register for this conference, including individuals from forty nine countries.

Children have participation rights from birth. They need to learn how, when, where and in relation to whom these rights can be expressed. Research on the social competencies of children has indicated, in general, that their capabilities have been underestimated. They can make choices, express opinions and understand relevant information at a tender age. Long-term, comprehensive perspectives are needed that support the learning of democratic principles and practices with applications beginning before the child starts grade school. Nursery schools and kindergartens have been able to establish basic democratic decision-making.

Rights require more than legal support

Accountability must be assured

Teacher preparation, parent education and the ability of the child

The meaning and fullness of life as a child should not be totally or even substantially sacrificed to the possibilities of a future state of development. A new child-image must be established that recognizes children as subjects, not objects. Research in developed countries has shown that when adolescence is treated as a holding or waiting period—a preparation period for the ‘real’ life to come later—the experience is closely related to youth culture problems. Children need the opportunity and richness of play, exploration, experimentation, fantasy and work meaningful to them. According to Buscaglia (1978):

What is meant by safe schools?

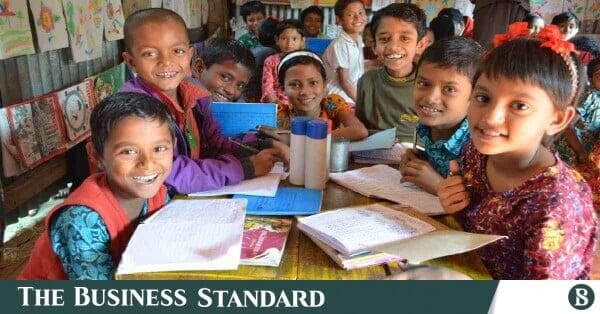

Every child in the world should have access to safe, quality and inclusive education. But over 500 million school-age children and adolescents live in countries where schools face threats. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child affirms that every child has a right to education. The purpose of education is to enable the child to develop to his or her fullest possible potential and to learn respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. The general principles of the conference which are relevant to education cover non-discrimination, the best interests of the child, the child’s right to life, survival and development, and the child’s right to express opinions. These principles can serve as a useful instrument in discussions on how to reform schools.

Education under attack: 90 countries pledge to make schools safe for children

A few years ago, a number of international organisations working on child welfare set themselves the task to find which, among the large number of possible interventions, would be the most effective for ending violence against children. This joint effort led by the World Health Organisation resulted in the INSPIRE package: Seven strategies for Ending Violence Against Children . Based on the evidence emerging from a large number of studies conducted across different world regions, it outlines what are the most effective policies and initiatives – most effective both in terms of outcomes and of cost effectiveness – that governments, international donors, and local civil society organisations should work on in order to prevent or minimise the damage caused by violence against children.

Seven strategies for ending violence against children identifies a select group of strategies that have shown success in reducing violence against children. They are: implementation and enforcement of laws; norms and values; safe environments; parent and caregiver support; income and economic

strengthening; response and support services; and education and life skills. More countries are taking action to protect children and teachers from attacks on schools. Ninety nations have now signed up to the Safe Schools Declaration - a commitment to safeguard education from violence - and many are clamping down on the military use of schools.